Television was infected with TV Specials in the 70’s. Any comic or singer worth a mic, who could fill a nightclub on a weekend night, would eventually be tossed an hour long TV Variety Show. Richard Pryor was becoming a huge presence on the standup circuit in the 70’s and in May 1977, two years after his triumphant and legendary hosting gig on Saturday Night Live, NBC aired the Richard Pryor Special? (By September that year, he was given an official show that ran 4 episodes)

The special was comprised of skits, celebrity cameos, music breaks (how about an appearance by “& The Pips“, KILLING their full service backup groove without need of lead singer Gladys Knight), and believe it or not, actual poetry. As the special starts, Pryor (fresh off a slave ship and tossed onto the plantation of his own network show) walks through NBC studios backstage considering different ideas for his first tv show while running into different recognizable character actors (LaWanda Page not dissimilar from Sanford and Sons’ Aunt Esther, Glynn Turman— then off the successful film ‘Cooley High’ and future staff-member in ‘A Different World’– and comic Shirley Hemphill, who… yeah, you probably wouldn’t know), including himself as a senior shoeshine vendor.

Some television in the 1970’s had unexpectedly sharp edges. Often, sitcoms would turn toward the camera to make a statement about any number of the social problems plaguing communities; drugs, gangs, teen pregnancy, Name Something.

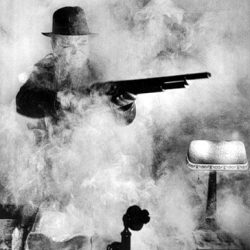

And right there during the Richard Pryor show, a sketch begins set in a neighborhood bar, occupied by four people, two men and two women. One man is the sober bartender, SNL cast member John Belushi, and one woman is seated by herself at a table, drunkenly nursing a cocktail. Pryor pops up from behind the bar as Willie, roasting each bar customer before they can roast him. The sketch is all funny until an adult walks into the room. Actor Arnold Johnson, husband of one of the bar flies, enters riled and humorless. He confronts his wife at the end of the bar for her commitment to drink over family. And when Pryor’s Willie approaches, the husband lets him have it– punches him to the floor of the bar, then angrily leaves pulling his intoxicated wife along behind him.

Belushi’s bartender gets Willie to his feet and gently sets him sail from the bar to back home, across the street. The theatrical set separating the bar from Willie’s front stoop is but inches away, yet Pryor as an actor lets us feel the agonizing block he has to walk before getting home to his wife, waiting and armed with rightful complaints. Willie is haunting because Pryor plays knows this drunk character all too well.

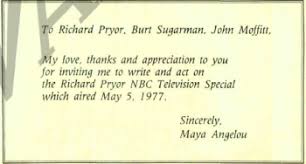

The door opens to a pink robed Maya Angelou: poet and writer, ‘relunctant actress’, who during this era appeared in the mini-series Roots and produced educational documentaries on early PBS, was also calypso dancer, music composer, and professor.

Pryor has little by way of any excuses to her. “I ain’t got time to stand up and listen to it, baby” he says before plunging face first into the couch, dissolving into a drunken stupor. This gives the spotlight to Angelou, who gets “to sit here and talk intimately to you like this every night.” Given the mic and spotlight of Willie’s subconscious attention, she goes to town.

What happens next is so unexpected as to feel like a mistake on live tv. It is as grounded and honest a monologue can get without veering into documentary. On screen in film and tv, women were mostly regulated to bracing, holding up and supporting male characters. They were encouraging girlfriends, supportive wives: women who cheered or complained but always stayed out of the way; annoyed yet patient of their ill-prepared, heroic men out making aggressively selfish and stupid choices.

Here, with ‘Willie’ having vanished into the dreamy arms of alcohol, she talks with what remains of her man, laying snoring and farting again, smelling like the bathroom in a brewery. She is not furniture tossing angry, not pushed to the end of her patience. She lets him in the house for another round of whatever this relation-shit is, and tries to figure things out. “Why do you drink so much, Willie?” she asks. One could imagine them as a sober, young couple without alcohol riding Willie’s back. One could also see Angelou’s character as a wife worth having. Is Willie proud of her? Does he deserve her? Or is his alcohol a coping mechanism? What is sober Willie like? What does he do? Come morning, is it she who is “sick, tired, disgusted”… or is it him?

This moment may not be the first time some serious message interrupted the laughs on a sitcom, but its certainly one of the most weighty and important moments in tv, because it acknowledges that your ‘funny drunk uncle’ or ‘life of the party coworker’ are not heroic and any laughs they garner lead to tears. (Willie couldn’t protect himself much less any of the women in the bar, and becomes useless to his wife back home. )They all have families who wait for them to return from their seance with the spirits of alcohol. What must people who’ve worked The Program think of tv’s flagrant celebration of alcohol and the culture of drinking? As a child, I saw my father and my cousin disappear into strangers when they’d drink. There was no laugh track to make anything better in my living room. Somewhere exists a world where Pryor was not an addict, who thrived as a comedian and actor anyway, a man successful and sober. When Pryor channels his wino and junkie characters, he signals to us in the audience the part of himself that isn’t so funny, the men in his life who were problematic. My father was my hero even when it was frightening to look into his eyes. Its not entirely alcohols’ fault, either. Perhaps Angelou’s character, as a black woman, fully understands that. For any man of color to soberly engage the world during that era of the 1970’s, an era growing out of the fresh graves of fighters for the civil rights movement, is a true hero, a genuine leader, who would have to leave their beautiful, encouraging wives home alone to wait for the revolution to come.

Watch the sketch in full on Youtube.

ONE MORE BRIEF NOTE ABOUT THE RICHARD PRYOR SPECIAL

Why don’t tv specials offer poetry any longer? Why can’t poets pop up on late night talk shows more often? Where is the creative commentary? Where is beauty? Truth?

Right in the center of the Richard Pryor Special, a poem by Langston Hughes (though not credited to Langston Hughes) is staged before us, entitled ‘Harlem Sweeties‘.

A stroll of black supermodels appear while verses of Hughes’ poem are read in voice over. The women introduce themselves as representative of a different shade of blackness.

Brown sugar lassie,

Caramel treat,

Honey-gold baby

Sweet enough to eat.

Peach-skinned girlie,

Coffee and cream,

Chocolate darling

Out of a dream.

They are all perfect in their imperfections and the moment itself a thing of beauty: a display of models in the day’s high fashion presented alongside spoken word poetry. The segment ends on the only model I looked up: Azizi Johari is still with us. She worked as a model, actress and was former Playboy Playmate for June 1975. She appeared in a scattering of movies and tv shows in the 1970’s and 80’s. You should treat yourself to the entire segment here.